Our health insurance system is sick. The moral and ethical condition of the Philippine Health Insurance Corp. (Philhealth), the country’s national health insurer, has been made widely known to the public, and the public has clearly made a judgement. Like most questions of individual virtue in systemic settings, however, the vices of its administrators are emboldened and emphasized by Philhealth’s own systemic faults.

Much of its financial troubles arise out of its design. Philhealth is not a medical institution. It is not an administrative agency. It is an insurance company, with government subsidy, a collection aspect, a claims and benefits distribution operation, and a reserve fund to administer. These are specialties that all ought to be optimized, or they will systemically affect each other negatively.

However, because these functions are all currently administered together, they do not benefit from the gifts of specialization. Another problem is that the company is perceived as a “health institution,” when most of its operations have very little to do with medical science. Rarely has the President of Philhealth been chosen from the insurance or the financial services industry. In fact, five of the past nine Philhealth presidents since 2000, starting with now Health Secretary Francisco T. Duque, were doctors.

To clean Philhealth up, we will have to set up systems where Philhealth’s general operations, its reserve fund, its claims and benefits distribution, and its collection activities are separately optimized. Where administration is tainted, faultily commingled operations can yield to diseconomies of scope, or what we in the finance industry used to call “diworsification.”

BASIC FINANCIAL INSIGHTS ON PHILHEALTH

The Universal Health Care (UHC) Law, or Republic Act No. 11223, was enacted February 2019 to provide universal health insurance coverage to all Filipinos. Funding the UHC Law has been the principal rationale for this representation’s efforts to champion sin taxes, as well as to propose comprehensive reforms in medical access and cost.

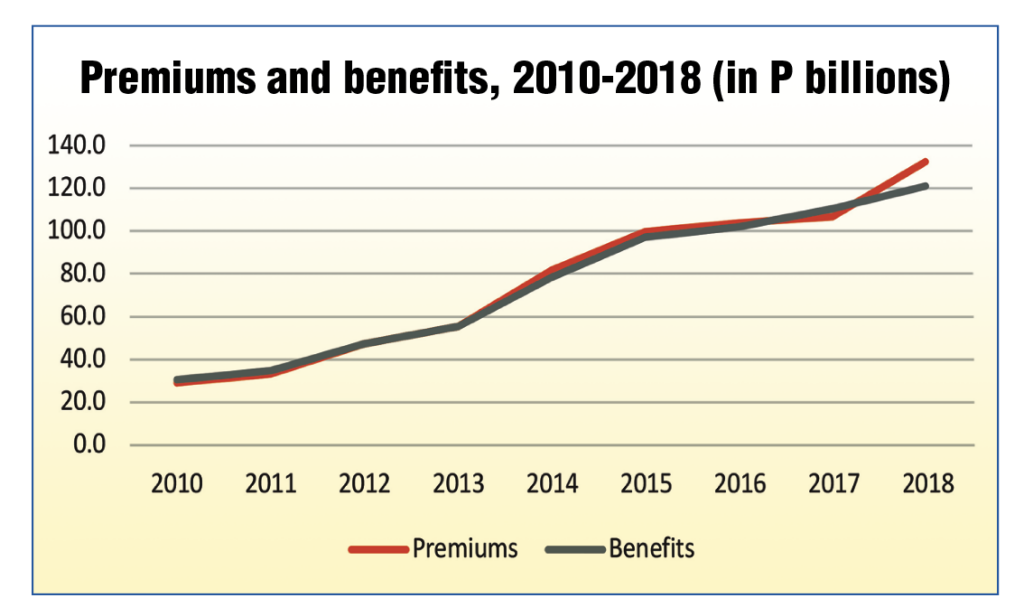

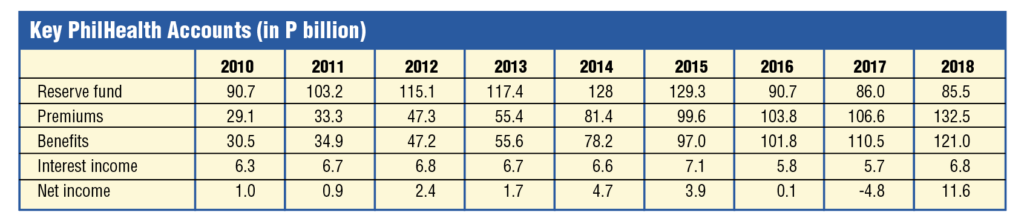

The basic accounts of Philhealth show that there, for the most part, the financial health of the company has been relatively in good shape, with premiums more or less matching benefits, and with the reserve fund consistently yielding a reliable flow of interest income.

Premiums and benefits have more or less been on track with each other, giving little reason for the decline in reserve fund over recent years. In fact, in 2018, a surge in surplus premiums (at around P11.5 billion) was seen. The fund should be expected to manage its finances in well and fortify its reserves during good years such as these, so that the health insurer can be prepared for bad years, such as COVID-19.

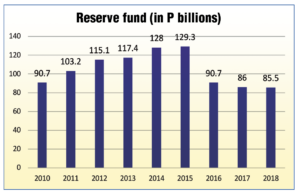

The reserve fund, however, has been shrinking, even when Philhealth has continuously posted a net income (except in 2017).

The reserve fund’s shrinking has been more remarkable considering that Philhealth’s net income has been steadily increasing, except in the period of 2015-2017. Net income dramatically increased in 2018.

A NOTE ON PHILHEALTH’S RECENT CLAIMS OF IMPENDING BANKRUPTCY

Philhealth executives have recently claimed that, based on their actuarial projections, the GOCC will be facing a P90 billion shortfall in 2020 and a P110 shortfall in 2021. This is an exaggerated claim. For the entire first semester of the year, Philhealth has sustained only a P5.99 billion loss, acceptable given the dire circumstances. Furthermore, the reserve fund has already hit P105.8 billion as of June 2020, an increase of P8.88 billion compared to the same period last year, meaning a strong fallback position is in place should the health insurer face more unpredicted costs due to COVID-19 claims.

This lends the insurer’s actuarial operation in question. If the P90 billion claim is correct, the DOH will have to sustain a shortfall of P84 billion in the second half, a loss never before seen in the health insurer’s entire corporate life. The actuarial accuracy of this projection is at best, suspect.

RESERVE FUND MANAGEMENT

The reserve fund was put in place to ensure that shortfalls during bad years can be covered. Part of the issue with Philhealth’s reserve fund mismanagement, however, stems from design. While most corporations would fill their “reserves” with accumulated equity, Philhealth’s reserve fund comes from funds set aside from current-year revenues.

Taking current-year revenues to set aside as reserves places operations in the financially awkward position of drawing from reserves (part of which has probably already been invested) if current-year claims are actuarially underestimated. This exposes operations to actuarial miscalculation, and, given the oddness of Philhealth’s actuarial projections, such miscalculations are very probable risks.

The UHC law’s provisions on reserve fund management could still be improved. Under current provisions, Philhealth sets aside “a portion of its accumulated revenues not needed to meet the cost of the current year’s expenditures as reserve funds.” This is prone to several layers of risks: actuarial miscalculation for current-year expenses, the moral hazards of having a fund that can be used for expenditures, the risks of unfavorably influencing market prices, downward, when Philhealth sells its equity holdings (which should be the most liquid among the investment reserve fund), among others.

A simpler, more rational approach, to ensure that profits during good years are used to cover losses in bad years is to simply accumulate all net income in the investment reserve fund, to be managed by the Bureau of Treasury, or a designate of the Monetary Board, to ensure that the best macroprudential standards are upheld. This would also ensure that regular operations and reserve fund operations are not unduly commingled.

QUESTIONS OF FAIRNESS IN PAYMENTS

Current payment contributions reflect a probably necessarily discriminatory regime, where the poor do not pay any direct premiums, and are instead covered by government subsidy, there are self-employed voluntary contributors, and there are formal sector contributors, who pay the bulk of Philhealth’s non-subsidy revenue.

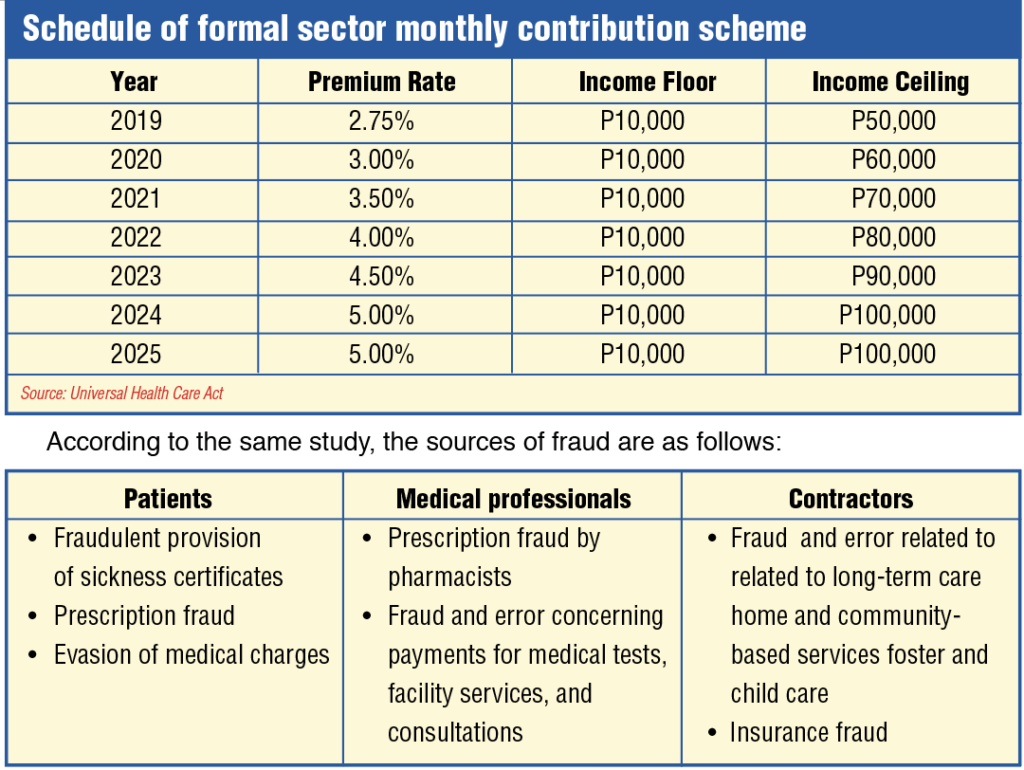

Increase in Philhealth contributions. Republic Act No. 11223, or the Universal Health Care Act, increased Philhealth contributions. Section 10 of the law states that Premium Contributions. – For direct contributors, premium rates shall be in accordance with the following schedule, and monthly income floor and ceiling: (see upper table)

The law defines “Direct contributors” as “those who have the capacity to pay premiums, are gainfully employed and are bound by an employer-employee relationship, or are self-earning, professional practitioners, migrant workers, including their qualified dependents, and lifetime members.”

This income scheme effectively means that, those earning an annual income of P120,000 a year will, by 2025, already be paying 5% of their income for Philhealth benefits, when the same income segment is exempt from personal income taxes (PIT) for the simple reason that the country considers them too poor to pay these taxes.

This premium scheme is extremely unfavorable to working families. The capped contribution scheme means that those earning more than P1,200,000 a year are effectively paying less and less premiums as a share of their income. This makes for a bizarre health premium regime where the very poor pay effectively no direct premiums (but pay indirectly through their consumption of excised products), the poor and middle working class pay the same percentage on premiums, and the rich and very rich pay less and less as a share of their income, the richer they get.

A simpler fix would have been to just tie the premium contributions to the PIT. In 2018, the formal sector paid P65.9 billion in premiums, implying around P32.95 billion in employee share. A simpler collection scheme that matches the progressivity of the recently reformed personal income tax scheme, and would have yielded the same revenues would simply have been a 3% levy on individual tax dues and a minimum P100/month employee share. This would have saved the minimum wage earner at least P4,800 a year in premiums, and would also have made the premium structure more attuned to changes in income.

A 5% levy on individual taxes, plus the minimum premium would have yielded around P46 billion in employee share, or around P92 billion in formal sector premiums. Considering the same expenses in 2018, this scheme would have also made enough surpluses to cover almost 60% of the government subsidy to Philhealth.

Premiums more closely tied to income are also more sustainable than the floor-and-ceiling approach in the UHC, as health expenditures tend to rise with national income.

Tying premiums with income taxes withheld also means that Philhealth can significantly outsource its collection function to the Bureau of Internal Revenue, which can simply charge a collection fee from Philhealth, instead of Philhealth having to maintain full collection operations.

SOME ISSUES ON CLAIMS AND BENEFITS

The most glaring cases of fraud in Philhealth appear to be in the management of claims and benefits. As with any insurance operation, the risk of insurance fraud is real and must be proactively managed by designing transparent and accountable systems. According to the Presidential Anti-Corruption Commission Commissioner Greco Belgica, around P153 billion, or almost a third of Philhealth claims, since 2013, have been lost due to fraud.

If this is true, Philhealth’s losses due to fraud are around 5 to 6 times the global average. According to a 2015 study by PKF Littlejohn LLP and the University of Portsmouth, the global average loss rate due to fraud is around 6.19% as a proportion of global healthcare expenditure.

To address these issues, our office has begun consultations and studies. The immediate rollout of the National Identification System, coupled with a national health database, with a one-patient, one-record system, would make it easier to spot cases of false identity, and fraudulent sickness declarations. Linking this with a national prescription database would also help identify and prevent overprescription.

To develop the infrastructure necessary for these databases, and to strengthen our primary care system, we also have proposed House Bill No. 7422 or the Philippine E-Health and Telemedicine Development Act of 2020. This would extend primary care to the remotest regions (preventing the higher costs of overspecialized care), and, if used to develop a national health database, would help prevent cases of fraud. Those who would organize fraud, whether inside or outside Philhealth, need to connive with more people, in an easily verifiable system, where anomalies can be identified with data analytics. If ever fraud happens in the telehealth system, we can more easily catch them

GOVERNANCE REFORM FOR PHILHEALTH

We disagree that privatizing universal health care is the solution for this problem. State insurance agencies can be reformed. Indeed, the cleaning up of the Government Service Insurance System (GSIS) from one of the most reviled public agencies, to a reliable and well-managed insurance operation with a very broad range of services to its constituent market, has been a remarkable success story. A mix of transparency mechanisms on procurement, beneficiary status, and service delivery has significantly improved GSIS governance and financial performance.

One of the GSIS’s model reforms has been entering into an agreement with the Philippine Statistics Authority (formerly National Statistics Office) to determine the status of GSIS pensioners. Thus, GSIS no longer requires its pensioners to visit any of its offices for the renewal of their active status to receive their monthly pension. In the absence of a fully operational National ID system, this is the next best substitute.

While the GSIS runs several health and deathcare operations, it does not necessarily have executives from the healthcare sector. Instead, most of its executives have extensive experience managing banks and financial institutions. Its board is also not necessarily inter-agency, ensuring that board members are full-time decision-makers whose sole and primary responsibility is to ensure the proper governance of the agency.

Considering that Philhealth has significant fiscal implications and is more an insurance agency with a massive investment operation than a health agency, we propose a greater role for and oversight by the Secretary of Finance. The board structure of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the US counterpart of Philhealth, is simpler: Four members serve by virtue of their positions in the Federal Government: the Secretary of the Treasury, who is the Managing Trustee; the Secretary of Labor; the Secretary of Health and Human Services; and the Commissioner of Social Security. Two other members are public representatives whom the President appoints and the Senate confirms.

The managing trustee is essentially the Chair of the Board. Considering the size of its insurance and investment operations, and considering the potential convergences with the Secretary of Finance’s oversight of the Insurance Commission for the insurance operations, and the Bureau of Treasury and the Securities and Exchange Commission for the investment operations, we propose that the Secretary of Finance also be designated as Chair of Philhealth under a reformed governance model.

As for transparency and audit, we recommend independent external audits be mandates for Philhealth, on top of audits by Commission on Audit. Philhealth has a history of being flagged by the COA (we have annexed audit findings from 2008 to 2017 herewith), but many of these issues remain unresolved. We recommend an accountability mechanism that involves identifying the correction and prevention of these and similar cases as performance indicators that the management will have to be measured against, for bonuses and retention.

CONCLUSION

We have broken down the operations and systemic problems of Philhealth around four areas: Reserve fund management, claims and benefits management, collection, and governance. Reforms in these areas can be carried out independently, but we will be proposing a comprehensive reform of Philhealth that encompasses these areas.

We have not found a compelling reason to privatize Philhealth, as this will almost certainly increase costs for the system. Furthermore, a privatized system would be difficult to make compatible with our public health care system. Under a public, single-payer system, we achieve convergences between public insurance and public health care.

We disagree with the “actuarial projection” that Philhealth will face record losses in 2020 and 2021. However, we recommend reforms in the premiums system to make premiums more progressive, equitable, and linked to income. Our review of existing studies leads us to concluding that income and health expenditures are correlated, and a scheme more linked to graduations in income would account for such correlation better.

We recommend that the reserve fund be managed by the Bureau of Treasury, and be managed independently of the insurance operation. We also recommend that instead of being drawn from current revenues, reserve funds be the accumulation of all retained earnings. This would allow income in good years to cover losses during bad years.

We also recommend anti-fraud measures, such as a national health database, a national prescription database, a one-patient, one-record rule, and links with the National ID system to prevent identity fraud, misdeclarations of sickness, and other fraudulent declarations. We also recommend the passage of House Bill No. 7422, or the Ehealth and Telemedicine Development Act of 2020, which would extend primary health care to remote regions and complement anti-fraud data gathering and analysis.

We also recommend several governance reforms, including a greater role for the Secretary of Finance as new Chair of the Philhealth Board (considering the convergences with insurance and investment oversight), independent private-sector audit of Philhealth on top of COA audits, and governance as a performance measure for bonuses and retention of officials. We will be filing measures that reflect these reforms in the coming days.