The first wide study of 18 countries in five continents found that high intake of carbohydrates increased risk of death and death from non-cardiovascular disease.

High carbohydrate intake is more than 60% of energy and was strongly associated with higher risk of total mortality in both Asian and non-Asian countries. Types of carbohydrates (refined vs whole grains) were not differentiated. (The Lancet, Vol 390, November 4, 2017)

This Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study is contrary to the prevailing opinion that high fat leads to higher risk of death and heart disease. Instead, higher intake of total fat and individual types of fat were each associated with lower total mortality risk in Asian countries and non-Asian countries.

High fat also lowered non-cardiovascular disease deaths and stroke. Neither was high fat related to major heart disease, heart attack, or death from cardiovascular disease (CVD).

These findings debunk the decades-long diet recommendation to limit total fat intake to less than 30% of energy and saturated fat intake to less than 10% of energy.

Results were unaffected by household income, household wealth, or the country’s economic level.

The researchers recommend that those with high carbohydrate intake eat less carbohydrates and eat more fats.

Replace carbs with fat

A high carbohydrate diet is usually accompanied by a low fat intake. But lower fat leads to higher risk of total mortality, non-cardiovascular disease death, and stroke.

A high carbohydrate diet is usually accompanied by a low fat intake. But lower fat leads to higher risk of total mortality, non-cardiovascular disease death, and stroke.

The strongest association on total mortality was found when carbohydrates are replaced with polyunsaturated fat , it lowers the risk of non-heart disease death by 16%. Food high in polyunsaturated fats are seeds, fish, nuts like walnuts, and corn oil.

When just 5% of energy from carbohydrate is replaced with polyunsaturated fat, the risk of death lowers by 11%.

Studies show that refined carbohydrates increase the risk of stroke. But when carbohydrate is replaced with saturated fat, this lowers stroke risk by 20%. Saturated fat comes from animal products and are solid at room temperature, like butter, cheese, and meat.

When carbohydrate is replaced with other fats and protein, it does not lower stroke risk.

Similarly, when carbohydrate is replaced with saturated fat, monounsaturated fat, or protein, there is no effect on CVD and risk of death.

Very low-carb diets, or less than 50% of energy, is not recommended because it does not show health benefits. Importantly, carbohydrates are needed to meet short-term energy demands during physical activity, so moderate intakes, like 50–55% of energy, is better than either very high or very low carbohydrate intake.

Why we thought high fat was bad

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the number one cause of death globally. Over 17.7 million people died from CVD in 2015, representing 31% of all global deaths. Of these deaths, an estimated 7.4 million were due to coronary heart disease and 6.7 million were due to stroke. (World Health Organization)

Over 80% with CVD are from low-income and middle-income countries like the Philippines. Diet is one of the most important modifiable risk factors for CVD and other noncommunicable diseases.

For decades, dietary guidelines focused on reducing total fat (<30% of energy) and saturated fat intake (<10% of energy).

This presumption was largely based on selective data of North American and European high-income countries, where saturated fat intake is limited (about 7–15% of energy), but total fat intake was high and people overeat. Since CVD was the major cause of deaths, it was concluded that high saturated fat led to higher risk of death from CVD. But results from this nutrient excess seems inapplicable to other regions with nutritional deficiency.

Doctors thought that if we replace saturated fat with carbohydrates and unsaturated fats, it will lower LDL cholesterol (the bad cholesterol) and therefore reduce CVD and its related conditions. However, this assumption does not consider the effect of saturated fat on other lipoproteins like HDL cholesterol, ratio of total cholesterol to HDL cholesterol, or on apolipoproteins, which could all be better markers of CVD risk and blood pressure.

The broader PURE study shows that nutrients have varying effects on different lipid fractions. So isolating the effects of diet on LDL cholesterol is not reliable in projecting the effects of diet on CVD events or on total mortality.

How PURE study is different

This PURE study tracks the impact of diet on total mortality and CVD in diverse settings, different races, education, and incomes for a total of 135,335 subjects ages 35–70.

This PURE study tracks the impact of diet on total mortality and CVD in diverse settings, different races, education, and incomes for a total of 135,335 subjects ages 35–70.

PURE countries include three high-income (Canada, Sweden, and United Arab Emirates); 11 middle-income (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, Iran, Malaysia, occupied Palestinian territory, Poland, South Africa, and Turkey); and four low-income countries (Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, and Zimbabwe).

Food patterns are culture dependent and generally related to geographical region rather than income region, so countries were categorized into seven regions: China, south Asia (Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan), North America, Europe, South America, Middle East, southeast Asia (Malaysia), and Africa.

In PURE, 52% of the participants ate a high carbohydrate diet (at least 60% of energy) and about 25% ate more or 70% of their energy from carbohydrate. This carbohydrate intake is higher than previous studies in North America and Europe.

This study represents a broad range of carbohydrate mean intake of 46–77% of energy, compared with previous studies with lower mean consumption and a narrower range of carbohydrate intake (35–56% of energy). This might explain the stronger association between carbohydrate intake and total mortality.

Most participants from low-income and middle-income countries ate a very high carbohydrate diet, especially from refined sources (such as white rice and white bread), which leads to increased risk of total mortality and CVD events. So recommending less carbohydrates for these income levels is practical if replacement foods from fats and protein are available and affordable.

Carbohydrate intake was highest in China, south Asia, and Africa. In south Asia about 65% ate at least 60% of energy from carbohydrate while 33% ate at least 70% of energy from carbohydrate. In China, 77% ate 43% of energy from carbohydrate. The highest fat consumed was in North America and Europe, Middle East, and southeast Asia. Protein intake was highest in South America and southeast Asia.

Low fat is not always better

PURE is the first large study to describe the association between low saturated fat intake (<7% of energy) and total mortality and CVD events.

The health benefit of replacing total fat with carbohydrate has been debated. Previous studies show that when fat was replaced with carbohydrate it did not lower the risk of coronary heart disease and even increased risk for total mortality. Furthermore, higher glycaemic load was associated with a higher risk of ischaemic stroke or an inadequate blood supply to the brain.

Thus, limiting total fat consumption is unlikely to improve health, and a total fat intake of about 35% of energy along with lower carbohydrate can lower risk of total death.

For individual fats, there’s an inverse relation between saturated fat with total mortality, non-CVD death, and stroke. There’s no evidence of an increase in major heart disease, heart attack, and CVD death. This suggests that the effect of saturated fat is more complex than previously assumed and the risks might depend on the amount of nutrient consumed.

There is no significant link between saturated fat and CVD when replacement nutrients were not taken into account. Even when saturated fat is reduced with the replacement of polyunsaturated fat, it did not affect total mortality.

PURE covers lower saturated fat intake (50% ate less than 7% of energy; 75% ate less than 10% of energy) compared with half of North Americans and Europeans (over 10% of energy). This shows a more accurate effect on total mortality and CVD events.

The inverse link between saturated fat and stroke are consistent with previous studies. It does not support the recommendation to limit saturated fat to less than 10% of intake, where a very low intake (below 7% of energy) can be harmful.

There is an inverse relation between monounsaturated fat and total mortality. This is consistent with randomised trials of the Mediterranean diet that show reduced risk of total mortality and CVD among those who ate higher amounts of olive oil and nuts. Monounsaturated fats are liquid at room temperature, but start to harden when chilled. It is found in plant food like nuts, avocados, and vegetable oils.

Higher polyunsaturated fat lowers total death rates and modestly lowers risk of stroke. This is consistent with the lower total mortality among US men and women and Japanese men.

Socioeconomic status based on education, household income, household wealth, and country income level, whether rural or urban, did not alter results. But it is possible that high carbohydrate and low animal products might simply reflect lower incomes.

Further areas of study

Some factors might alter the results of the PURE study. It did not quantify the types of carbohydrate (refined vs whole grains) consumed. Low-income and middle-income countries ate mainly refined carbohydrate. It also did not measure trans-fat intake which might affect results, especially in replacement analyses. Lastly, it assessed polyunsaturated fat mainly from food rather than from vegetable oils, which might have different health effects than those observed.

In conclusion, PURE found that a high carbohydrate intake was associated with a higher risk of total mortality, whereas fats including saturated and unsaturated fat were associated with lower risk of total mortality and stroke. Fat did not affect cardiovascular disease events.

In this light, current global dietary guidelines and personal practices that limit fat should be reconsidered. Still, high carbohydrate consumption should be lowered.

Food manufacturers tout low fat versions of classic recipes but consumers remain unaware of the high carbohydrate content. For example, the Skinny Cow low fat ice cream has 4.5 grams of fat but a high 28 grams of carbohydrate. A cup of white rice has no fat and about 40 grams of carbohydrate.

Experts recommend a very low 20 to 50 grams of carbohydrates a day for obese, diabetics, and those who want to lose weight.

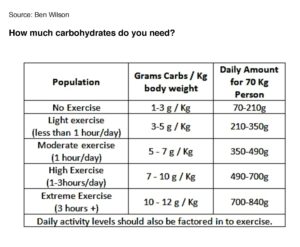

A sedentary person can eat 70 to 120 grams of carbohydrates a day. If you exercise less than an hour a day, you can eat up to 350 grams. Moderate exercise of an hour a day allows you to eat up to 490 grams a day. The more you exercise, the more carbohydrates you can eat.

But we cannot just isolate carbohydrates from other factors of health. Our body relies on multiple nutrients from protein, fats, vitamins, and minerals. The synergy of food, our body, exercise, and other factors like our environment is still not fully understood. So a healthy lifestyle, a nutritious diet, regular exercise, and adequate sleep is always recommended.

There is no single solution to good health. Just as we cannot blame just one factor like carbohydrates or fat for disease or death. There has to be a concerted effort of many positive actions. In any case, for better health and longer life, moderation and balance is key.

IVY DIGEST

Ivy Lopez is a lawyer turned journalist who studied in the Jesuit-run Ateneo de Manila University and the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School.

Ivy’s column Ivy Digest serves the busy reader by reviewing worthwhile publications and covering relevant issues in business, law, education, leadership, psychology, parenting, technology, and career advancement.