Reading is the foundation of learning because 80% of the information we gain is visual. We cannot navigate and thrive in our world if we cannot read. More importantly, reading makes us smarter.

“If one had to choose a single measure of the academic quality of a school system, the average reading score of its graduating seventeen-year-olds would serve. Verbal scores at that age predict students’ college and career readiness and their later economic success.” (E.D. Hirsch Jr, Why Knowledge Matters—Rescuing Our Children From Failed Educational Theories, 2016)

Reading proficiency translated to better performance in other areas like math. One independent comparison of SAT (Scholastic Assessment Test) scores, a US test for college admission, showed that 44% of perfect scorers in reading also scored highly in math. But perfect math scorers did not excel in reading.

“So these SAT figures suggest that literature proficiency is more likely to be accompanied by mathematics achievement than the other way around. Humanities scholars might well argue that if we want to improve agility in algebra, more time should be spent discussing novels and poems.” (Andrew Hacker, The Math Myth and Other STEM Delusions, 2016)

Early is not better.

The race to teach young children to read early is misguided and can be harmful to a child. While early readers have proven advantages over late readers, this is true if the child reads good books continuously and consciously. But if the early reader does not develop the habit of reading regularly, the early start is negated. What matters is the consistent engagement with excellent books.

How does forcing a child to read early harm him? If we push the child to read before he is ready or interested, we can turn him off from reading in general. When reading exercises are presented prematurely as a chore rather than as enjoyment, the child views reading as work and will not choose to do it in his leisure time. The point is to rear lifelong readers who read for fun and learning.

Reading develops a child’s mental process as he follows the story, figures out the characters, predicts the outcome, imagines the places and people described, and pretends himself into the story or situation. If more children were read to, then more children would have sharper thinking.

“More children would have the critical thinking, interest, information, tolerance, and empathy fostered by literacy.” (Esmé Raji Codell, How to Get Your Child to Love Reading—For Ravenous and Reluctant Readers Alike, 2003)

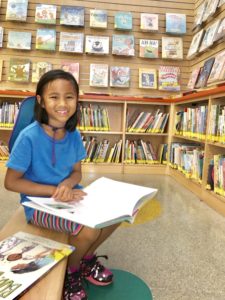

Read aloud to grow bookworms

The best way to introduce books is by reading aloud to the child from an early age. Picture books stimulate the child visually and trains him to read a book from left to right, to turn the page from front to back, and to realize that the story progresses from beginning to end. As the child grows older and gains more understanding, the words in the book are slowly linked to the illustrations and the child learns to enjoy the characters and the plot.

But the most important benefit of regularly reading to the child is the comfort that it provides while he is nestled in his parent’s arms. He knows that this is his time to be with his mom or dad and he feels special that they share this allotted time.

This bonding time forms a pleasant memory. So he will likely associate reading with pleasure, “an association that is necessary if order to maintain reading as a lifelong activity” (Codell)

Studies show that reading aloud to our child is the most important thing we can do for his intellectual growth. While we read, we can explain the context of the story, ask how the character probably feels, and what might happen next. We can answer the child’s questions and define words or expressions. This is the essence of engagement that we seek to develop in the reading child.

It’s not just the mere act of reading, or reading just anything. Reading good literature develops mental processes necessary for critical thinking, prediction, problem-solving, imagination, and creativity. It makes the reader more intelligent.

“Comprehension involves making hypothesis about what the words mean. It applies to listening as much as to reading. That’s why listening ability in early grades is the key to reading ability later on. In listening the young mind does not have to be slowed down by the new chore of decoding, and so can learn new words and concepts efficiently. Reading aloud to children and classroom discussion should play a big role in the early grades.” (Hirsch) [emphasis added]

Jim Trelease advocated the importance of reading aloud to children after his investigation found that when a child is read to he becomes a lifelong reader. He self-published his findings in The Read-Aloud Handbook in 1979 that has since been adopted by educators and updated in 2013.

Trelease found that when parents read to a child it produces many benefits: it conditions the child to associate reading with pleasure; builds background knowledge for all other subject areas like science, history, geography, math, and social studies; gives a reading role model; creates empathy; increases vocabulary; lengthens attention span; stimulates imagination; and strengthens academic performance. It also develops the child’s self-esteem and emotional development.

“A reading test is a test of general knowledge and vocabulary; it gauges a student’s ability to operate effectively within the public sphere.” Hirsch

Vocabulary is so important for the student because it is the main basis for IQ scores, college assessment exams, and school success. In adult life, a wider vocabulary leads to effective writing, impressive speaking, greater reading proficiency, and sharper problem-solving abilities.

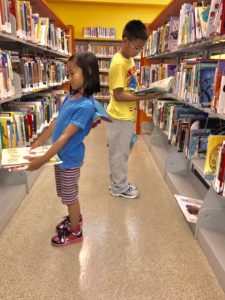

Unfortunately, there is a notion that we should only read aloud to young kids. So as the child gets older and becomes a more independent reader in later elementary, there is a tendency to stop reading to them.

“This is a fallacy, and a very dangerous one: The fall-off of read-aloud can be correlated to the fall-off of interest in reading, with 90 percent of fifth-graders spending less than 1 percent of their time reading. Eight-graders average a little less than two hours a week reading, including homework. While an older child may know how to decode the words, that’s only the beginning of a life of reading, and without read-aloud, it could also be the end.” (Codell)

“More mature readers may need the flow of discussion to encourage prediction skills, to understand character development, to determine cause and effect. They benefit from the model of an adult reading with proper pacing and attention to dialect and punctuation, and learn to troubleshoot by watching an adult guess from context or look up an unknown word.” (Codell)

Even if we have been remiss in reading to our child, we can read with them at any point in their childhood and teen life. They will still reap the many benefits of shared reading.

“Read-aloud has the power not only to sustain but to resuscitate an interest in and affection of the printed word for children of all ages,” writes Codell.

Though reading aloud to our child sounds simple, it takes great commitment and time. It’s hard to muster the energy at the end of a tiring day to sit down and share a book with our child at bedtime. But even if we cannot do it daily, we should try to do it as often as we can.

“Daily read-aloud fulfills an emotional need of your child’s, to be close and to feel safe, and gives him the chance to discuss concerns with you. In stories, your child can see conflicts resolved and be reassured that even the biggest fear or foe can be overcome through love, contemplation, and bravery. Through reading, your child can also find comfort and escape and the opportunity to mature. Your child deserves all that. Your one child is precious, your one child is worthy.” (Codell)