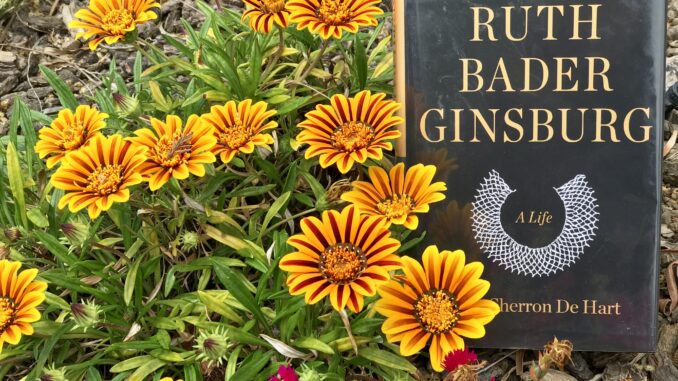

By Jane Sherron De Hart

Hardcover, 722 pages, 2018

Alfred A. Knopf

This is the most comprehensive RBG biography. It also details the case law for her landmark Supreme Court cases.

Ruth was a formidable lawyer who battled sexism in her career.

“Admitted to the college [Cornell] in a ratio of one to four, they [women] had to have a higher grade point average than their more numerous male peers.” RBG finished first in her class.

She was one of nine women in Harvard Law. “Schools that trained students for law, medicine, or other traditionally male professions had quotas that limited the number of women to a maximum of 10 percent.”

“Once through the needle’s eye, the token women admitted faced further obstacles in securing scholarship money. Jobs for which they were trained were in even shorter supply. For those who secured employment, the biggest challenge still awaited: combining career and family in a society that offered scant support to women who tried to do both.”

When Harvard found out Ruth was married after they granted her scholarship, they asked for her father-in-law’s financial statements.

“If a male student were in a comparable situation, would the Law School ask for the financial statement of the wife?” asked Ruth angrily.

Harvard Law Dean Griswold would “welcome” each female law student with, “Why are you at Harvard Law School, taking a place that could have gone to a man?”

At Harvard, there was no female restroom in the main hall. Ruth would run nearly a block to use a converted janitor’s closet. “Asbestos dripped from the ceiling.” It lost her valuable minutes during timed law exams.

During her third year in law, supportive husband Marty was diagnosed with cancer. This distressed Ruth greatly because her mom died of cervical cancer in after she graduated from Cornell.

Marty needed cancer treatment in New York. Given the extraordinary circumstances and her outstanding grades, Ruth requested Harvard’s Vice Dean if she can be allowed to finish her last year at Columbia but still get a Harvard law degree. Denied. Ruth appealed to Dean Griswold, but he too denied her.

So Ruth transferred to Columbia Law to take care of Marty, take notes for him, and help him pass his classes. Despite all the stressors, Ruth still tied for first place in her graduating class in 1959.

RBG was the first to be in two law reviews: Harvard (the first female) and Columbia. She had an outstanding record and was first in her class. If she were a man, she would have been a coveted hire. Instead, RBG was dismayed that no one wanted her.

“To be a woman, a Jew, and a mother to boot” was just “a bit much” she said.

Neither did RBG fit the expected image of a lawyer—male, self-assured, and tough.

“Viewed through these lenses, Ginsburg—with her small size, soft voice, youthful image, and feminine appearance—did not measure up.” Ruth was “rather diffident, modest and shy” and Ruth was told clients would be uneasy with a woman.

Good thing Ruth’s Columbia professor Gerald Gunther helped Ruth get a job.

“Gunther then called every federal judge in the Southern District. Only two would agree to an interview, and one declined to make an offer.” They thought RBG would constantly run home to her daughter.

Gunther made a deal with Judge Palmieri: he threatened never to recommend another Columbia clerk and if RBG didn’t work out, she could be easily replaced by another talented man from her class who was already employed.

When RBG taught at Rutgers Law School, she discovered that she was paid less than the male faculty. Dean Heckel said they were underfunded and anyway “she had a husband to take care of her, so it was only fair that she receive a lower salary than a man with a family to support.” contrary to equal pay federal law. RBG was on a yearly contract and wanted to be renewed, so she did not argue.

When RBG became pregnant with her second child, boy, she hid it for fear she won’t be renewed at Rutgers.

When RBG cared for her sick dad and kid while she juggled teaching and motherhood, she never asked for special consideration or a leave of absence because she was afraid it might jeopardize her prospects of tenure at Rutgers.

RBG was often dismissed at discussions where she was introduced as wife and mother or Mrs. Ginsburg instead of a lawyer.

Under affirmative action, Harvard offered RBG a visiting professorship in 1971. The next year, she became the first tenured female faculty at Columbia Law School.

In 1972, RBG and Marty won Moritz, her first gender discrimination case, in the appellate court, which became a movie. Her former Harvard Dean Griswold, now the Solicitor General, failed in his appeal to the Supreme Court.

She headed the ACLU Women’s Rights Project for which she argued six gender cases before the Supreme Court. She was a Court of Appeals justice for 13 years before she was appointed to the SC.

RBG penned numerous well-reasoned articles, casebook, and briefs on gender discrimination. She is a stalwart advocate for women’s rights and equality.

@IvyDigest on FB & IG