By Antonio S. Lopez

Two decades in modern Philippine history stand out—the 1980s (1980-1989) and the 1990s (1990-1999). They changed the fate and fortune of the nation—from bad to worse, then worse to worst, with between, exhilarating ups and terrifying downs. The ups were moments of triumph and pride. The downs were times of despair and descent into darkness.

The Tale of Two Decades reminds you of Charles Dickens’ “The Tale of Two Cities”:

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way—in short, the period was so far like the present period.”

Trouble, turmoil, turbulence

Unlike Dickens’ Paris and London in his time, the Manila of the 1980s and the 1990s was in far graver trouble, turmoil and turbulence than anyone can imagine today. And so was the rest of the Philippines.

The only era that could perhaps compare with those two decades was the Philippine Revolution of 1896 to 1898. As it turns out, that time for struggle for freedom and independence was one of hope and deliverance, much unlike the twin decades of the 1980s and 1990s which were more like endless journeys of distress and desperation.

Common issues

The 1980s and 1990s had many things in common—global economic instability in general and for the Philippines in particular, recurring political instability, vexing high incidence of poverty (50% for three decades), revolting income inequality among the people, uncontrollably high population growth rate (2.75% average per year in 1970-1980 and 2.4% in 1980-1990), and the dominance of business monopolies in sensitive and strategic industries and even in such mundane ancient enterprises like retailing and banking.

Earlier, the decade of the 1970s started off with a major economic crisis. The Philippines faced its first debt crisis accompanied bya balance of payments deterioration which started in 1968.

These problems eventually brought about a 50% devaluation of the peso and double digit inflation never before experienced in Philippine history, according to the World Bank.

Per capita income drops from $848 to $587

Per World Bank data,per capita GDP for 1980-1982averaged $848.From 1983 to 1990, however, per capita GDP tapered off to $587mainly due to the combined effects of the peso devaluation and slow growth in output production.

The 1980s began with a three-year global recession. The deepest and most severe economic slowdown since World War II was marked by massive production cuts, mass unemployment, and runaway inflation in the United States and much of the rest of the world.

To curb inflation, interest rates rose and credit markets tightened. This was bad for the Philippines which had financed its development and purchases of precious crude oil with an unprecedented borrowing spree using easy-money petrodollars.

The world in the 1980s

Here is how Wikipedia describes the 1980s, globally:

“A key event leading to the recession was the 1979 energy crisis, mostly caused by the Iranian Revolution which caused a disruption to the global oil supply, which saw oil prices rising sharply in 1979 and early 1980. The sharp rise in oil prices pushed the already high rates of inflation in several major advanced countries to new double-digit highs, with countries such as the United States, Canada, West Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom and Japan tightening their monetary policies by increasing interest rates in order to control the inflation.

“These G7 countries each, in fact, had ‘double-dip’ recessions involving short declines in economic output in parts of 1980 followed by a short period of expansion, in turn followed by a steeper, longer period of economic contraction starting sometime in 1981 and ending in the last half of 1982 or in early 1983. Most of these countries experienced stagflation, a situation of both high interest rates and high unemployment rates.”

The Dewey Dee debacle

In the Philippines in 1981, recalls the World Bank, “the financial system was shaken by the fleeing of a rich financial tycoon leaving millions of dollars in debt in various Philippine banks. This generated panic among money market investors and depositors and led to massive withdrawals. The financial panic eventually brought many investment houses, off-shore banking units and commercial banks into trouble.”

This was the Dewey Dee scandal of Jan. 9, 1981. He fled the country with $85 million in unpaid debts—to 16 banks, 12 investment houses, and 17 other financial institutions, plus $4 million of post dated checks. Most were unsecured loans. A textile magnate and banker, Dee was hit hard by the downturn of 1979-1980, losing big bets on sugar, gold, and dollar speculation.

Dictator reelected a second time

The Dewey Dee debacle aside, in June 1981, Ferdinand Marcos sought to establish his democratic gravitas by holding an election, having “lifted” on January 17, that year, his nine-year-old martial law but retaining his one-man decree-making powers and the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus. With executive and legislative powers in his hands, the wily lawyer was a veritable dictator. Marcos, of course, won the election, with a lopsided and a record 80% of the vote against an unknown retired general, Alejo Santos.

On June 30, 1981, Marcos was inaugurated for the third time as president. The inauguration had then US Vice President George H.W. Bush, Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, future president of China Yang Shangkun and Thai Prime Minister Prem Tinsulanonda in attendance. Bush declared what became an infamous praise for Marcos: “We love your adherence to democratic principles and to the democratic process.”

Marcos visits the US in 1982

For a while, it seemed Ferdinand Marcos had weathered the unwieldy financial storm of 1981. In September 1982, amid rumors of ill-health, the strongman paid a state visit to Washington DC where he was toasted by President Reagan.” It was Marcos’s first visit to the US since he became president in 1966.

“Our two peoples enjoy a close friendship, one forged in shared history and common ideals. In World War II, Americans and Filipinos fought side by side in the defense of freedom—a struggle in which you, Mr. President, personally fought so valiantly,” Reagan told Marcos at the mid-morn welcome ceremony at the South Lawn of the White House.

Reagan added: “The values for which we struggled-independence, liberty, democracy, justice, equality—are engraved in our constitutions and embodied in our peoples’ aspirations. Today our ties remain strong, benefiting each of us over the full range of our relations. Politically, we tend to view many world issues the same general way. Yours, Mr. President, is a respected voice for reason and moderation in international forums.”

Security relationship

“Our security relationship is an essential element in maintaining peace in the region and is so recognized. This relationship, one of several we have in the Western Pacific, threatens no one but contributes to the shield behind which the whole region can develop socially and economically,” the US leader, aware of the strategic importance of the two US bases, Clark and Subic, hosted by the Philippines. “Mr. President, under your leadership the Philippines stands as a recognized force for peace and security in Southeast Asia through its bilateral efforts and through its role in ASEAN, which is the focus of our regional policies in Southeast Asia,” Reagan said.

For his part, Marcos replied: “For, Mr. President, I come from that part of the world wherein the poorest of the world’s population live. I come from that part of the world that cherishes an image of America with its ideals, its dreams, its illusions. I come from the Philippines, a part of Asia which has been molded along the principles of American democracy. We learned to love these ideals and principles, and we lost a million of our people righting for them in the last war.”

“We have always stood by these ideals. We shall continue to do so, whatever may be the cost—at the risk of our fortunes, our lives. But more important of all, our honor will stand for the ideals of democracy that is our legacy from the United States of America,” Marcos assured.

The hypocrisy of such exchanges of goodwill and friendship would unravel four years later, on the night of Feb. 25, 1986, when US Senator Paul Laxalt (R-Nev), February 1986, admonished the defeated Marcos: “I think you should cut, and cut cleanly. I think the time has come.”

“I am so very, very disappointed,” Marcos muttered wryly.

The 1983 debt moratorium

In October 1983, the Philippines sought a debt moratorium, the first Asian country to restructure its maturing debts since the international debt crisis began to intensify a year earlier. In New York, the group of creditors led by the International Monetary Fund confronted the team of Prime Minister and Finance Minister Cesar Virata with a question: “Where is the missing $600 million in your reserves?”

The central bank had been found to have overstated its international reserves by $600 million by double counting its dollar funds. Governor Jaime Laya was ousted from the central bank and transferred to the Department of Education, perhaps, to teach kids the latest in math.

At the time of the 1983 90-moratorium the Philippines’ usable reserves went below $1 million, barely enough to buy 38,000 barrels of OPEC crude.

Crude oil price zooms

Crude oil jumped six-fold in price from $1.82 in 1972, when Marcos declared martial, to $11 in1974, in just three years. This was the First Oil Shock. The Second Oil Shock came in 1978-1980 when average crude almost tripled in three years, from $12.79 in 1978 to $35.52.

Oil went on to scale $109.45 a barrel in 2012 before collapsing to $41.47 with COVID-19, before stabilizing at this writing at $65.74 in 2021.

In 1983, interest payments had exceeded the new inflow of capital by about $1.85 billion. By July, the central bank had to devalue the peso, by 30%, to P11.11, from P8.54.

The Aquino assassination

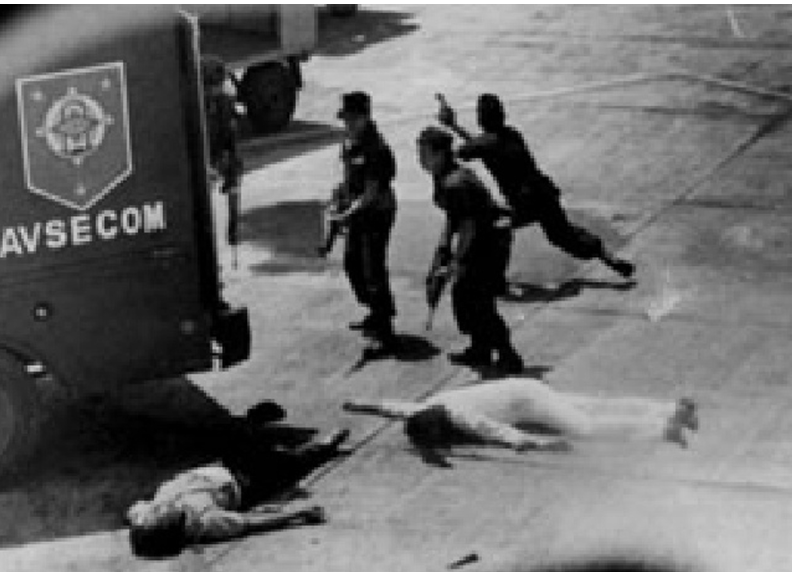

Two months earlier, on Aug. 21, 1983, the popular opposition leader Benigno S. Aquino Jr. was assassinated while descending from his plane at the Manila International Airport tarmac. The assassin or assassins came from the pro-Marcos military escorts who fetched Ninoy from his China Airlines seat.

The assassination set off an unprecedented political and economic crisis.

During the 1980s, or from 1980 to 1989, the Philippines’ average economic growth, as measured by the increase or decrease in the value of goods and services produced each year or Gross Domestic Product (GDP), was 2.01%. Deduct a high population growth rate 2.4% per year and the per capita growth was negative— at -0.4%.

Economic growth was erratic during the 1980s. It began with a hopeful 5.14% rate in 1980, only to drop a paltry 3.42% in 1981, 3.62% in 1982, and 1.87% in 1983 as the global recession and stratospheric interest rates overseas took their toll.

By 1984 and 1985 a perfect storm of challenges finally collapsed the entire Philippine economy. Negative growth was a mindboggling — 7.32% in 1984 which growth decline was repeated in 1985, with another -7.3%.

The lost decades

Thus, the 1980s were La Decada Perdida, the Lost Decade.

Still, the same tragedy happened with the 1990s—1990-1999, another Lost Decade.

The average GDP growth rate during the 10 years was 2.75%. Deduct the population growth rate of 2.4% per year, and the per capita growth was an infinitesimal .35%, a third of 1%.

The 1990s began growth with an uneasy 3.03% only to turn negative in 1991, with -0.578%.

A base effect growth reflected a 0.338% gain in 1992 as Fidel V. Ramos took over as president in July that year. Steady Eddie nurtured economic growth with 2.11% in 1993, 4.38% in 1994, 4.67% in 1995, and reach a five-year high of 5.84 in 1996 and 5.18% in 1997.

Then the Asian Financial Crisis struck. And growth went back to negative territory, -0.577 in 1998, with the populist actor-turned-politician Joseph Estrada taking over from the West Pointer Ramos.

GDP per capita growth in 20 years: one-twentieth of one percent

Together, the 20 years of the 1980s and 1990s betray a negative growth rate of -.05%, a crucifying but pointless rate 1/20th (one-twentieth) of one percent.

Between 1960 to 2008, neighboring economies in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) such as Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand (ASEAN-4) grew at a rate of around 4% per capita.

In 1981–1990, the average annual change of Philippine per capita GDP was a negative 0.6%; in contrast, Thailand grew 6.3%, overtaking the Philippines.

In the 10 years before that, in the 1970s, economic growth was a robust 5.6% average –5% during 1970-1974 and 6.2% during 1975-1979.

Foreign debts under Marcos

Marcos began his presidency in 1966 with only $700 million in foreign debts. The foreign obligations ballooned to $2.3 billion in 1970, $4.1 billion in 1975, doubled in two years to $8.2 billion, then levelled at $24.4 billion by 1982. By 1984-1985, the Philippines had its first recession since the post-War era.

By the time Corazon Cojuangco Aquino took over as president in 1986, the debts were at a record $26 billion, rising some more to $29 billion by 1989.

The Philippines remained at ground zero, stagnant, for 20 solid years. This is a country that until 1965 was the second largest economy in Asia, after Japan.

Per the Asian Development Bank, in 2003, the richest 20% of the Philippine families received more than half of the national income, while the poorest 20% accounted for only one-twentieth. In 1985,the top decile of the population had more than 15times the income of the lowest decile.

What happened

How did it happen that a country so rich in natural resources and so endowed with truly talented people who are warm, smiling, 85% literate, and God-fearing, had have to endure two consecutive Decadas Perdidas?

Filipinos became poor, and the poor poorer still. Poverty rose from 49% of families in 1971 to 58% by 1985, although as a percentage of the population, it declined from 64% to 54% during the same period. Joblessness was a nagging problem, exceeding 12% in 1985.

Reported the World Bank: Prices remained unstable and vulnerable to shocks in the economy throughout most of the eighties. Inflation rates remained at two-digit levels (except for the periods 1975-1978, 1983and 1986-1988)averaging 14.7%. (The highest inflation rate, 50.3% was in 1984 at the height of the balance of payments crisis and the lowest at 0.8% in 1986with the euphoria over the ouster of Marcos.

Underperformer

According to ADB, “the Philippines has consistently underperformed most of its regional neighbors in providing productive employment opportunities to its growing labor force.

Since the early 1990s, the unemployment rate in the Philippines has remained persistently high and has fluctuated between 8–12%, compared with 1.5–4.4% in Thailand and 2.5–5% in Malaysia. Even among the employed population, the level of underemployment was high at 22.7% in 2006, compared with 4% in 2000 in Thailand.”

“Hong Kong, China; Republic of Korea; Singapore; and Taipei,China—often referred to as newly industrializing economies (NIEs)—have undergone remarkable economic transformation and modernization since the 1960s and now export manufactured products on a global scale.

The four NIEs in East and Southeast Asia are regarded as models of successful industrialization and are often referred to as economic miracles. In contrast, the Philippines did not make a similar transformation,” said the Manila-based ADB.

The Philippines’ development performance during the past several decades has been less impressive than that of many of its East and Southeast Asian neighbors.

The Philippines was rich until the 1960s

In the 1950s and 1960s, the country had one of the highest per capita gross domestic products (GDPs) in the region—higher than the People’s Republic of China, Indonesia, and Thailand. However, the Philippines had fallen behind.

According to a 2007 ADB, between 1950 and 2006, the Philippine GDP in 1985 prices, expanded 11.2 times—an average growth of 4.4% each year. But the growth rate was never smooth. The economy, for instance, contracted in 1984–1985, 1990, and 1998.

Accounting for growth in population, which rose from about 19 million in 1950 to 87 million in 2006, for an average annual growth of about 2.75%, the Philippines in 1960 had a per capita GDP of about $612.

By this measure, the Philippines was ahead of Indonesia, with a per capita income of $196 and Thailand, with $329. The Philippines trailed Malaysia; Hong Kong, China; Singapore; Republic of Korea; and Taipei, China. By 1984, Thailand’s per capita GDP of $933 had overtaken the Philippines’ $908.

In 2006, per capita GDP of the Philippines stood at $1,175, compared with Thailand’s $2,549.

During 2001–2006, the Philippines posted its highest average per capita GDP growth of the past 2.5 decades, at 2.7%; at that rate, per capita GDP could double, but in about 26 years.

Natural resources

The Philippines is rich in natural resources. Land planted in rice and corn accounted for about 50% of the 4.5 million hectares of field crops in 1990.

Another 25% of the cultivated area was taken up by coconuts, a major export crop. Sugarcane, pineapples, and Cavendish bananas also were important earners of foreign exchange. Forest reserves have been extensively exploited to the point of serious depletion. Archipelagic Philippines is surrounded by a vast aquatic resource base.

In 1990 fish and other seafood from the surrounding seas provided more than half the protein consumed by the average Filipino household. The Philippines also had vast mineral deposits.

In 1988 the country was the world’s tenth largest producer of copper, the sixth largest producer of chromium, and the ninth largest producer of gold.

The country’s only nickel mining company was expected to resume operation in 1991 and again produce large quantities of that metal. Petroleum exploration continued but discoveries were minimal, and the country was required to import most of its oil.

Prior to 1970, Philippine exports consisted mainly of agricultural or mineral products in raw or minimally processed form. In the 1970s, the country began to export manufactured commodities, especially garments and electronic components, and the prices of some traditional exports declined. By 1988 nontraditional exports comprised 75% of the total value of goods shipped abroad.

There were internal problems as well, particularly in respect of the increasingly visible mismanagement of crony enterprises.

In 1990, the Philippines had not yet recovered from the economic and political crisis of the first half of the 1980s. At P18,419, or $668, per capita GNP in 1990 remained, in real terms, below the level of 1978. A major thrust of Aquino’s 1986 People Power Revolution was to address the needs of impoverished Filipinos.

Half of Filipinos poor

In 1985 slightly more than half the population lived below the poverty line, about the same proportion as in 1971. The proportion of the population below the subsistence level, however, declined from approximately 35% in 1971 to 28% in 1985. The economic turndown in the early 1980s and the economic and political crisis of 1983 had a devastating impact on living standards.

The countryside contained a disproportionate share of the poor. More than 80% of the poorest 30% of families in the Philippines lived in rural areas in the mid-1980s. The majority were tenant farmers or landless agricultural workers. The landless, fishermen, and forestry workers were found to be the poorest of the poor. In some rural regions—the sugar-growing region on the island of Negros being the most egregious example—there was a period in which malnutrition and famine had been widespread.

According to a 1984 government study, 44% of all occupied dwellings in Metro Manila had less than 30 square meters of living area, and the average monthly expenditure of an urban poor family was P1,315.

Of this, 62% was spent on food and another 9% on transportation, whereas only P57 was spent on rent or mortgage payments, no doubt because of the extent of squatting by poor families.

The richest 20% gets 50% of the wealth

In 1988, the most affluent 20% of families in the Philippines received more than 50% of total personal income, with most going to the top 10%.

Below the richest 10% of the population, the share accruing to each decile diminished rather gradually. A 1988 World Bank poverty report suggested that there had been a small shift toward a more equal distribution of income since 1961. The beneficiaries appear to have been middle-income earners, however, rather than the poor.

The state-protected monopolies were dismantled, but not the monopoly structure of the Philippine economy that existed long before Marcos assumed power. In their privileged positions, the business elite did not live up to the President’s expectations.

As a consequence, unemployment and, more importantly for the issue of poverty, underemployment remained widespread.

Cory Aquino had a troubled presidency

According to the World Bank, “in 1986, the Philippine economy emerged from the martial law rule with serious imbalances.

The consolidated public sector deficit reached about 6% and external debt was close to 100% of gross national product. Foreign reserves fell to a level equivalent to less than one month of imports. Inflation hit 50% in 1984 before falling to 23% in 1985.

Real GDP recorded two consecutive years of negative growth, at –7% (in 1984 and 1985).

The central bank was saddled with massive liabilities, and the finance sector was plagued by huge nonperforming loans of the two government financial institutions— the Development Bank of the Philippines and the Philippine National Bank.

Social indicators were just as disappointing: unemployment was high and poverty was pervasive.”

Ninoy’s widow, Corazon Cojuangco Aquino was bedeviled by eight coup attempts, two of which were the bloodiest in the country’s history in 1987 and 1989.

There were other shocks, reported the World Bank: “Aprolonged drought lasting over the winter and spring months of 1989-1990substantially reduced crop output. The drought was also partly responsible for shortages in power availability which in turn reduced growth in industrial output. A strong earthquake in July of 1990caused considerable damage in Central Luzon. Turmoil in the Middle East caused the price of oil to jump byalmost 50%. A major volcanic eruption in June 1991 (Pinatubo) wrought extensive damage in several thousand acres of forest, farmland, cities, infrastructure, and US bases in Luzon.”

Cory assumes power

Cory assumed power in February 1986 without the benefit of a rightful election. She served for six years and four months. During her presidency, the country was plunged into the most severe energy crisis in its history.

Blackouts of up to 18 hours were a daily occurrence. Hence, Cory acquired the monicker “The Queen of Darkness.”

The electricity shortage brought forth economic slowdown and deterred investments, thus fueling inflation, promoting joblessness and overall despondency and poverty.

Today, we still suffer from the after effects of that crisis, by paying among the highest-priced electricity in the world.

Under Cory, the communist New People’s Army grew to unprecedented strength, up to 35,000 armed regulars, and reaching a level of strategic confrontation with the government.

She revived the Muslim separatist movement. The country was riven by discord. After six years, Filipinos became poorer than they were in 1986. Economic growth was stunted.

A democracy icon

Yet, today, Mrs. Aquino is known to the world as an angel, a freedom fighter, the Filipino Joan of Arc, the Mother of Democracy, and the woman who inspired the Philippines’ most peaceful revolution, People Power I, and the restoration of democracy in some 30 other countries under a dictatorship.

Mrs. Aquino is often credited for the now legendary EDSA People Power of Feb. 22-25, 1986.

She was in Cebu hiding in a convent during the first and most dangerous night of People Power, on Feb. 22, 1986.

Her son was too engrossed with many other things to have participated, too. I was at People Power I as a foreign correspondent.

The Aquino family had been the biggest beneficiary of People Power. They were awarded two presidencies totaling 12 and a half years, more than enough compensation for what opposition leader Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr. did in his political lifetime, which was to heckle and needle President Marcos during 17 of his 20-year presidency.

Marcos blamed

In 1983, Cory had blamed Marcos for her husband’s assassination and launched a destabilization campaign. Upon United States prodding, the strongman was forced to call a snap election to end bring the crisis, in February 1986.

Marcos was confident he would win the election. In 1982, the President still had the support of US President Ronald Reagan.

The Philippine economy was stable, having weathered what could have been a crippling downturn. Basic services were in place. But Ninoy’s murder turned things upside down.

Sensing Marcos was very sick (he was, having undergone two kidney transplants in 48 hours in August 1983), Ninoy Aquino attempted to return in 1983 and grab power from the President. The opposition senator was instead felled by a bullet at the airport tarmac.

On the first day of EDSA I, Feb. 22, 1986, I was lucky to be both in Cebu, for Cory’s civil disobedience afternoon rally, and Manila, for the first night of Enrile’s breakaway coup.

Enrile had no troops, just about two dozen RAM soldiers. His shock troops were us, foreign correspondents, numbering about 40.

Greed triggered EDSA

Not many people know it but EDSA I was triggered by greed and was won by a lie. The crowds that massed on EDSA on Feb. 24, 1986, Monday, and Feb. 25, Tuesday, were there not to stage a revolt but to hold a picnic. June Keithley had announced on radio at 7 a.m. of Feb. 24 that the Marcoses had left. It was a lie. In their glee and feeling that finally it was all over, people trooped to Edsa to celebrate.

The greed arose from a Chinese forex trader who violated the peso-dollar trading band imposed by the then unofficial central bank, the Binondo Central Bank managed and headed by then Trade and Industry Secretary Roberto V. Ongpin.

Ongpin had the erring trader arrested and loaded into a van. Unfortunately, the forex trader died.

Unfortunately again, the trader happened to be a man of then-Armed Forces chief Fabian C. Ver. Angered, the dreaded military chief had 22 of Ongpin’s security men arrested.

They were marching in full battle gear and dressed in SWAT uniform at about 4 a.m. inside Fort Bonifacio when arrested on Feb. 22, 1986, a Saturday.

At 11 a.m., at the Ministry of Trade and Industry, Ongpin went looking for his security men. He called up then-Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile who was with the Club 365 at the Atrium in Makati. Enrile thought the arrest of the 22 Ongpin security men, who turned out to be RAM Boys of Col. Gringo Honasan, was part of the crackdown against the plot to oust Marcos.

Planned in 1982

The putsch was being planned by Enrile and his RAM Boys as far back as November 1982. Marcos’s defense chief had heard rumors that the Armed Forces Chief of Staff, General Fabian Ver was planning a military junta to take over from the ailing Marcos.

Saturday morning of Feb. 22, 1986, Enrile summoned his boys to his house on Morada Street, Dasmariñas Village. There they plotted their next moves. They decided to make a last stand at the armed forces headquarters, Camp Aguinaldo in Quezon City.

At 2 p.m., Enrile called then Vice Chief of Staff Lieut. Gen. Fidel V. Ramos. “Are you with us?” JPE asked Eddie. “I am with you all the way,” the latter assured.

It was not until late in the evening that Saturday (Feb. 22) that Ramos actually joined the rebellion at Camp Aguinaldo. He had contacted his loyal PC-INP commanders, like Rene de Villa in Bicol, and Rodrigo Gutang in Cagayan de Oro and found to his dismay no troops could be readily airlifted to Manila to reinforce Enrile’s men, who were undermanned and under-armed.

Cory learned about the brewing rebellion at 4 p.m. the same Saturday in Cebu. She had led a destabilization and boycott rally there, which I covered.

After hearing about rumors of the Enrile defection, I went to the Mactan airport to book a flight to Manila. I landed in Manila shortly after 9 p.m. With Boy del Mundo of then UPI, I took a taxi to Camp Aguinaldo.

I was surprised to find the camp commander welcoming us with open arms. Enrile and Gringo had no troops at that time. Enrile had made a deal with Marcos—No shooting on the first night. Also, foreign correspondents were to be allowed inside Camp Aguinaldo.

Inside the Defense Ministry headquarters, Enrile and Ramos were giving an extended press conference. I asked if Cory Aquino called them up. Enrile said yes. “What can I do for you?” she asked. “Nothing, just pray,” Enrile replied.

Marcos won the February 1986 snap election

After Cory got the presidency, Namfrel made recount of the votes cast in the February snap election.

The tally still showed Marcos was the real winner, not by two million votes, as canvassed by the Batasan, but by 800,000 votes as recounted by Namfrel.

In the Comelec-sanctioned official count, the legal and official winner was Marcos, by a margin of 1.7 million votes.

It was thought Marcos had cheated because his Solid North votes were transmitted very late to the tabulation center at the PICC. Two Namfrel volunteers were hanged in Ilocos.

The Ilocano votes were enough to overwhelm Cory’s lead in Metro Manila and other places. The canvassers claimed Marcos was cheating and so led by the wife of a RAM major, walked out, as if on cue.

The day before the celebrated incident, we, foreign correspondents, had been alerted about the planned walkout and to be there to cover it.

Cory Aquino didn’t have any participation in the four-day People Power revolt of Feb. 22-25, 1986 or Edsa I.

Marcos’ legacy

As for the fallen Marcos, Marcos was perhaps the most charismatic of all Philippine presidents when democrats were still fashionable in elections and statecraft.

He embodied the best in the modern Philippine leader and was the nearest epitome of a great president.

He was a scholar with a keen sense of history, a genuine war hero with more medals than Audie Murphy, a bar topnotcher even while reviewing in jail, a great orator with a booming baritone, endowed with a political ideology and an eidetic memory (he once delivered a prepared speech to a joint session of the US Congress direct from memory). He had zeal and fervor to make his country great.

He entered politics in 1949 and campaigned for congressman, promising his northern Luzon common folk: “Elect me your congressman now and I’ll give you an Ilocano president in 20 years.”

He won as congressman and went on to serve for three terms. He was elected senator in 1959, was reelected in 1963 and became Senate president.

He was elected president in November 1965 and won reelection in 1969, the first president to do so.

In 1972, he declared Martial Law, ensuring his rule for 20 years, the longest by any Philippine president. His 20-year rule is notable for many things, aside from the usual gripes about corruption and dictatorship.

On the economic front, Marcos was the first to achieve rice self-sufficiency, the first to score a 8.9% economic growth (in 1973), the first to manage the country’s energy problem properly, the first to design a major industrialization program, and the first with a genuine land reform with an all-encompassing target of land transfers.

Average GDP growth during his 20-year regime was 3.8%; inflation, 10.3%.

According to Juan Ponce Enrile, a close ally of 21 years before he rebelled against him in 1986, “Minus the alleged corruption, Marcos was the most productive president we ever had.”

JPE enumerated what FM has done:

Marcos initiated the expansion of irrigation systems all over the country, the expansion of the infrastructure of the country like the Philippine Friendship Highway from Aparri to Zamboanga, the development of our port systems, the expansion of our air capability, the modernization of the military organization, and land reform.

Many of the plans being followed for the present infrastructure of the country were products of the Marcos period.

“In the field of international relations, Marcos initiated the one-China policy to the chagrin of Taiwan, opened relations with Moscow, shortened the lease on the American bases from 99 to 25 years, reduced the hectarage of the bases, and required the Americans to pay rent. He was able to preserve the national integrity in spite of the Moro National Liberation Front. He initiated the first tax amnesty, which was the most successful tax amnesty, and initiated the coco levy system to replace the aging coconut tree population. Today, the coco levy is now worth P100 billion. He brought the country closer to many countries because of his adoption of satellite. We solved the rice crisis, the cooking oil shortage, the gasoline crisis. Without the stain of corruption, Marcos was a great president,” Enrile told me.

Enrile was widely perceived as the jailer of President Aquino’s father, the popular opposition leader Senator Benigno S. Aquino Jr. (who was in jail for seven years and seven months), and at one point was accused of plotting to remove his mother, Corazon Aquino.

No wonder, Noynoy Aquino jailed JPE as soon as Cory’s son became president.